The boys are going to Vegas! (In theory, as long as we get our act together soon and plan it). And since poker might actually be one of the least degenerate things one can do in Vegas, it makes sense to study up and prepare to become a crusher. A few people have asked me recently about the most effective way to do some poker cramming in a reasonably short amount of time (say 25 hours). Despite receiving this question many times, it’s always been surprisingly difficult for me to answer.

I strongly believe that the best way to get better at poker in the long run is to just study GTO (Game Theory Optimal) poker with some kind of solver. (There’s a whole separate debate about theory vs exploits, which I won’t get into here). But “learn to copy the solver” is an approach that is slow, takes a while to realize decent payoff, and can be pretty unintuitive. It feels like one should be able to supplement this study by first learning some simple frameworks and heuristics that help interpret solver outputs and generally think about the game. So I turned to YouTube to try to find some good materials.

I was disappointed. One unfortunate reality about the poker ecosystem is that good instruction like this is hard to come by. The most easily accessible form of poker content comes in the form of vloggers who are hardly even serious players. Alternatively, there is a decent amount of content from high-stakes online pros, but is is complicated and usually assumes viewers have a lot of background knowledge. Even channels claiming to tailor to “low stakes online players” will be targeting people who have spent a decent amount of time on poker. When your experience thinking about EV is mostly centered around comparing the price of a box of Costco cookies to your buy-in, it’s not so productive to spend a lot of time talking about blockers in some arcane spot.

Nevertheless, the trip must go on, and poker is more fun when you’re winning, so I started doing a little thinking about how to simply and intuitively introduce some core game theory concepts. The hope is that building up from foundational theory can turn beginners into winning $1/$2 players with a relatively small amount of up-front time investment. I think this isn’t as lofty a goal as it sounds, because I truly believe the average low stakes live player is pretty awful. The only thing you must understand in order to follow the rest of the post are the rules of poker. Let’s jump in:

Toy Game #1

I’m going to start with poker’s most classic toy game. It’s not an overstatement to say that this is the foundation of all of poker game theory; I think everyone trying to learn GTO must first understand this thoroughly.

Let’s define ranges for Ivey in-position (IP) and Oscar out-of-position (OOP).

(IP = In Position = last to act, OOP = Out of Position = first to act)

Ivey’s IP Range’: AA, QQ.

A range refers to hands a player could possibly have in some spot, along with the relative probabilities that they have each of those hands. In this case, the above range means that Ivey has either AA or QQ randomly with 50% probability.

Oscar’s OOP Range: KK

SPR: 1

SPR = stack to pot ratio. With two players in the pot, this refers to the effective stack, which is the lesser of the players’ stacks. If player 1 has 100 chips, player 2 has 200 chips, and the pot is 100 chips, the SPR is 100/100 = 1. SPR is the fundamental way you should think about bet sizing and the pot in poker, and almost always dominates dollars (awful) or even big-blinds.

Board: 22233

The definition of a Nash Equilibrium is that no party can gain EV by unilaterally changing their strategy, given that the opposing strategies are fixed/known. Let’s think through the Nash for these two players.

Oscar starts. What should he do?

It’s pretty trivial to see that Oscar should start by checking. Ivey knows what Oscar has and gets to act with perfect information; if Oscar bets, Ivey simply gets to fold QQ and call AA. So by betting, Oscar makes the pot bigger only when he is going to lose, which is bad. So Oscar checks.

Facing a check, what should Ivey do?

With AA, Ivey should bet. He knows he is winning, and maybe Oscar will call a bet! This strictly dominates check, which would instead prevent Oscar from ever paying Ivey more chips.

Now what should Ivey do with QQ? Suppose for now that Ivey has the thought “well I know I have the worse hand, so I’m just going to give up here.” Ivey checks behind, loses the pot, and takes a bite of his Costco cookie.

Let’s pause at this iteration of strategies:

- Oscar: starts by checking

- Ivey: Bets AA, Checks QQ

- Oscar: Facing a bet → Ivey has AA → Oscar loses → always fold.

Note that in all cases, no more money is going into the pot. The current set of strategies are functionally the same as both players flipping over their hands at the start and each winning 50% of the time.

Let’s consider the scenario we outlined above more carefully and try to determine if it’s a Nash. We need to consider whether anyone has incentive to unilaterally change strategies with any part of their range.

Oscar: starts by checking

No incentive for Oscar to deviate here, we established earlier that betting is bad.

Ivey: Bets AA

This also seems fine. Ivey wins no matter what, and can’t get any MORE ev by checking behind.

Ivey: Checks QQ

Wait! We win 0 units if we check, but if we bet, we know that our opponent’s current strategy is to fold, so we’d win the full pot = 1 unit. So we should actually always bet QQ!

Let’s reiterate our nash from Oscar’s perspective given Ivey’s new deviation to bet QQ. We start by checking and always face a bet. Given Ivey’s new strategy, we know that he has QQ 50% of the time and AA 50% of the time. Our EV of folding is 0. Our EV for a call is \((0.5 \times 2 + 0.5 \times (-1)) = 0.5 > 0\). So now we should always call! (Our opponent is overbluffing).

It turns out that the adjustments we are making above are simply too large, but a solver will use a very similar iterative process (using something called Counterfactual Regret Minimization) to converge on an equilibrium. Here we can use the principle of indifference to produce a Nash. Simply, KK needs to call at a frequency that makes QQ indifferent between bluffing and giving up, and QQ needs to bluff at a frequency that makes KK indifferent between calling (bluff catching) and folding.

KK EV for folding is 0. So we want to compute QQ bluff freq such that:

$$ KK_{\text{ev_fold}} = \text{KK}_{\text{ev_call}} $$

$$ 0 = \text{KK}_{\text{ev_call}} $$

$$ 0 = P(\text{AA} \mid \text{p1 bets}) \times (-1) + P(\text{QQ} \mid \text{p1 bets}) \times 2 $$

$$ 0 = \frac{1}{1 + \text{QQ_bluff_freq}} \times (-1) + \frac{\text{QQ_bluff_freq}}{1 + \text{QQ_bluff_freq}} \times 2 $$

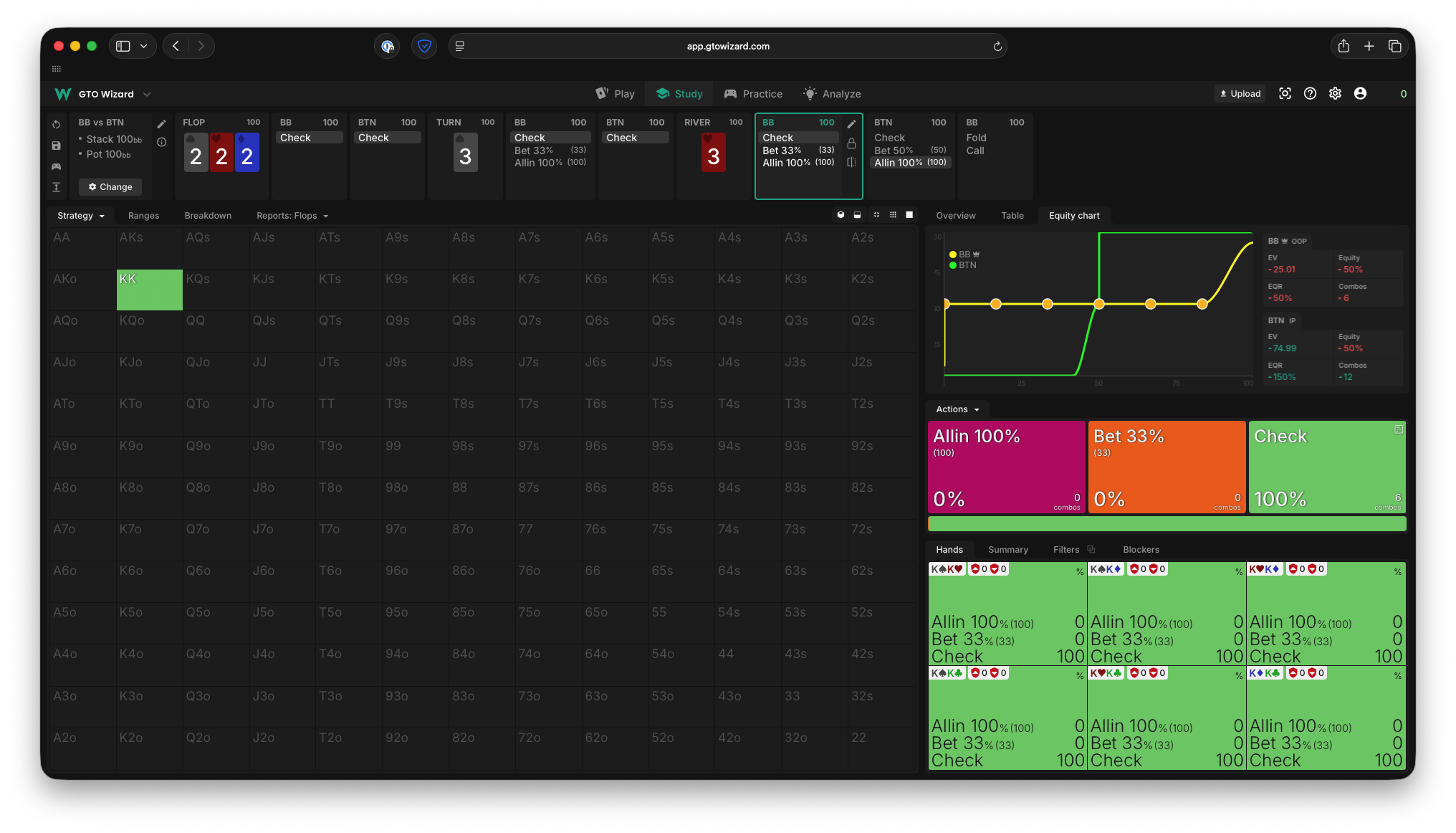

We can do some simple algebra here and get $\text{QQ_bluff_freq} = 0.5$.

We also know that Oscar must make Ivey indifferent between betting and checking QQ in order for this to be a Nash. Otherwise, Ivey would have incentive to deviate towards whichever action was better with his hand! So we can compute Oscar’s KK call frequency similarly:

$$ QQ_{\text{ev_giveup}} = \text{QQ}_{\text{ev_bluff}} $$

$$ 0 = \text{QQ}_{\text{ev_bluff}} $$

$$ 0 = P(\text{fold} \mid \text{p1 bluffs}) \times 1 + P(\text{call} \mid \text{p1 bluffs}) \times (-1) $$

Solving, $\text{KK_call_freq} = 0.5$.

Framework: Minimum Defense Frequency and Bluff-To-Value Ratio

The solution we came to above is a direct function of the SPR. When Ivey uses a pot-sized bet, Oscar must call half the time to make the opponent’s bluffs indifferent.

Minimum Defense Frequency (MDF): The minimum frequency a player must defend in order to make the opponent indifferent to bluffing with any two cards.

\[\text{MDF} = \frac{\text{Pot}}{\text{Pot} + \text{Bet}} = \frac{1}{1 + \text{Bet Size as fraction of pot}}\]

In our toy game: \(\text{MDF} = \frac{1}{1+1} = 0.5 = 50%\).

This is exactly the frequency KK called at! If KK called any less, QQ could bluff always and be profitable. If it called any more, QQ would never want to bluff.

Bluff-To-Value Ratio: To make the caller indifferent between calling and folding, we derive a similar equation for Ivey:

\[\frac{\text{Bluffs}}{\text{Value}} = \frac{\text{Bet}}{\text{Pot + Bet}}\]

In our toy game, with a pot-sized bet: \(\frac{\text{Bluffs}}{\text{Value}} = \frac{1}{1+1} = \frac{1}{2}\), so we need 1 bluff for every 2 value combos. Ivey has 1 value combo (AA) and therefore needs 0.5 bluff combos. He can achieve this by simply betting QQ half the time.

Intuitively, these are two sides of the same coin, and are just fancy ways of describing the Nash frequencies.

Examples with different bet sizes:

- Epsilon bet: MDF = 100%, Bluffs:Value = 0:1 (0% bluffs, 100% value)

- 0.5x pot bet: MDF = 67%, Bluffs:Value = 1:3 (25% bluffs, 75% value)

- 1x pot bet: MDF = 50%, Bluffs:Value = 1:2 (33% bluffs, 67% value)

- 2x pot bet: MDF = 33%, Bluffs:Value = 2:3 (40% bluffs, 60% value)

- Infinite bet: MDF = epsilon, Bluffs:Value = 1:1 (50% bluffs, 50% value)

Larger bets are paired with higher bluff frequencies, and also result in lower calling frequencies. But hands with 100% equity still make more money by betting large in theory! This is a general pattern that is important to remember.

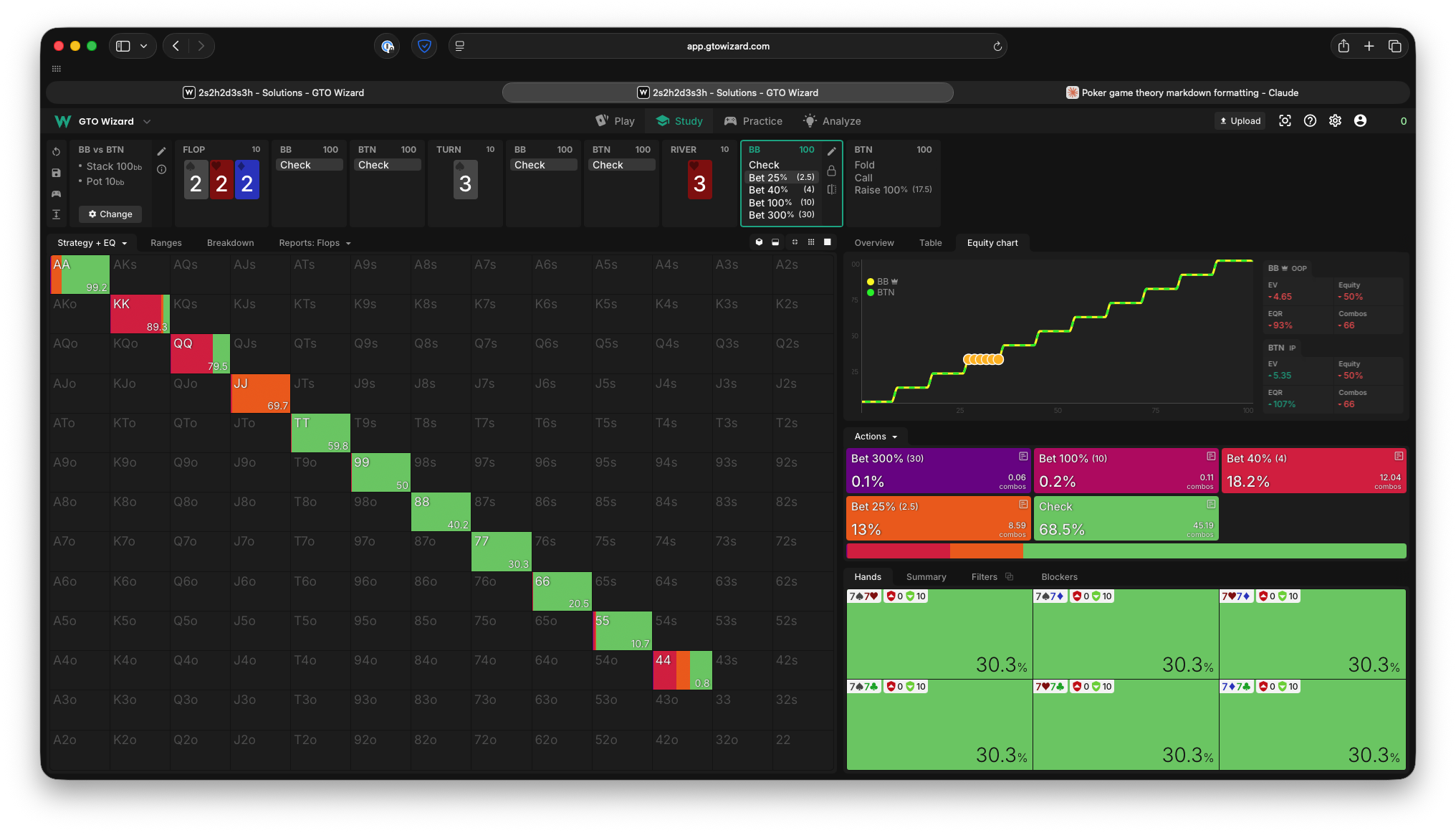

And the solver confirms our solution:

Commentary

There are a number of insightful takeaways from this relatively simple game.

-

Some quick definitions first:

- Equity: How often a hand/range would win if both player’s just flipped over their cards right now and dealt out the rest of the board.

- Equity realization: \(\text{EQR} = \frac{\text{EV_as_frac_of_pot}}{\text{equity}}\)

- Polar: Ranges that contain hands with either very high or very low equity vs the opponent’s range. In this example, AA had 100% equity and QQ had 0%.

- Condensed: Opposite of polar; ranges that contain hands with very middling equity. In this example, KK had 50% equity.

- Bluff-catcher: Any hand that beats all of your opponent’s bluffs and loses to all of their value. Traditionally refers to hands on the river, because equities are not so binary on earlier streets (you might have a draw, for example).

-

Bluff Catching

- Against balanced ranges, bluff-catchers are indifferent between calling and folding. In order for this to be true, calling must be 0 EV.

- I put this at the top because it is the most important. The first question to ask when you have a bluff-catcher is: do I think my opponent is over or under-bluffing? If you have a clear answer to that question, stop all further thought processes and either pure call or pure fold your hand.

-

There are no loss leaders in poker.

- Hands mix actions only when they are indifferent between those two actions. If KK were to start calling 1% less, QQ would snap towards bluffing always, not just slightly more often. You would repeat the equations I set up comparing the EV of bluffing vs giving up and discover that one is just strictly better.

-

Reducing your opponent’s hand to a bluff-catcher is equivalent to winning the entirety of what’s currently in the pot.

- EV is zero-sum here, and must sum to what’s currently in the pot. A bluff-catcher has 0 EV, so the opponent must be making the entire pot in EV with their range when you have a bluff-catching hand.

-

A more subtle follow-on: polar ranges have better equity realization than condensed ranges.

-

What were the Equity/EVs of the ranges given our Nash strategies above?

- Equity: Ivey: 50% Oscar: 50%.

- EV: Ivey: 0.75, Oscar: 0.25.

- EQR: Ivey: 150%, Oscar: 50%.

That’s interesting… both players had the same equity, but one has much larger EV! more on this in a bit.

-

-

Who should bet?

- Polar ranges/hands have an incentive to put money into the pot. In some sense they are at an information advantage and get to play “perfectly”.

- Condensed ranges/hands have an incentive to keep the small pot and get to showdown. They’re at an information disadvantage and have to “play defense”.

A whole toy box: games 2-N

I came up with a few illustrative extensions of this toy game, each of which highlight different concepts. These are harder to solve in the laborious way we did above, so I’m going to use a mixture of intuition and solver screenshots as we go through them:

2. What happens if we increase the SPR to 10 rather than 1? How do the EVs change?

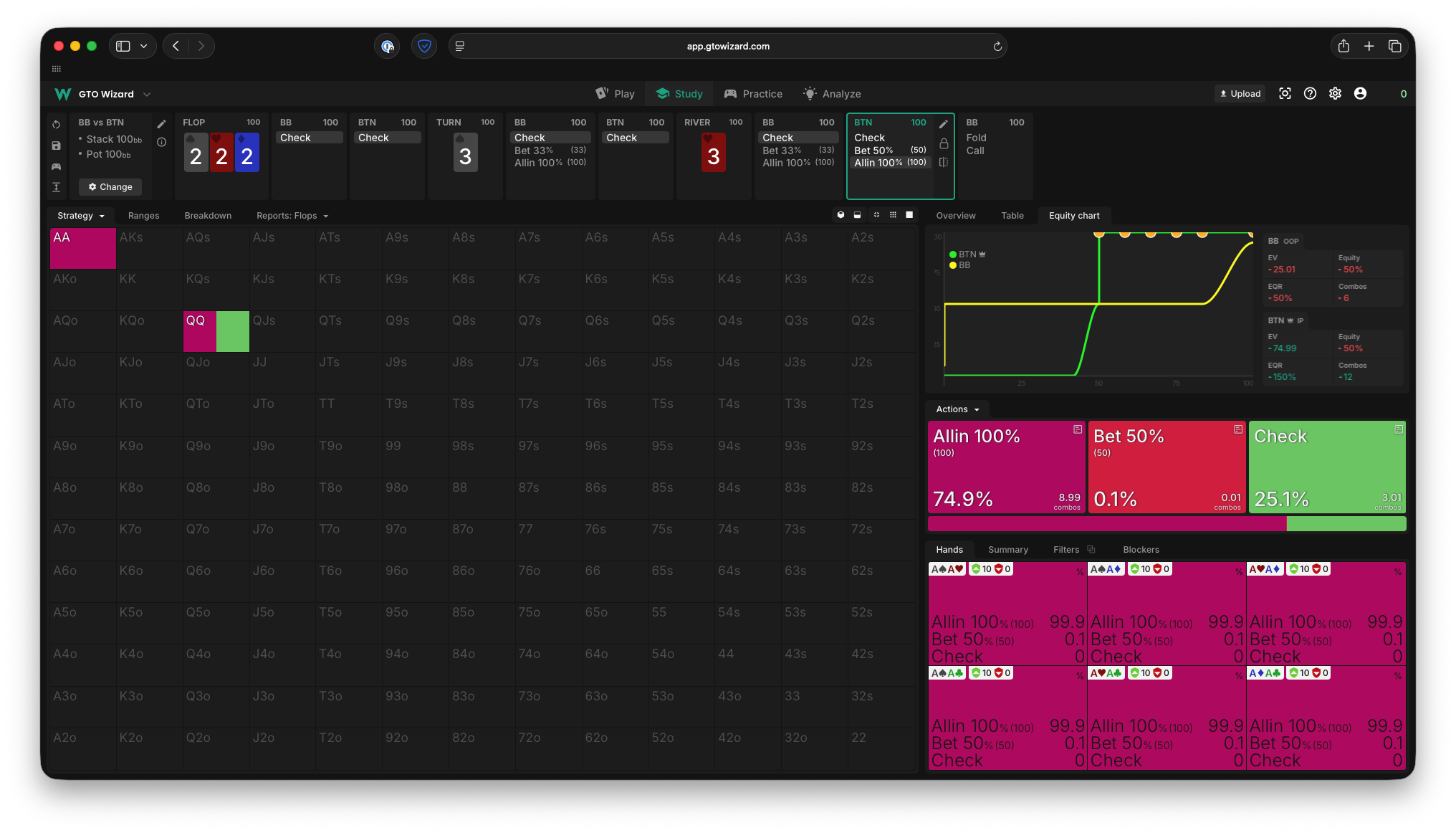

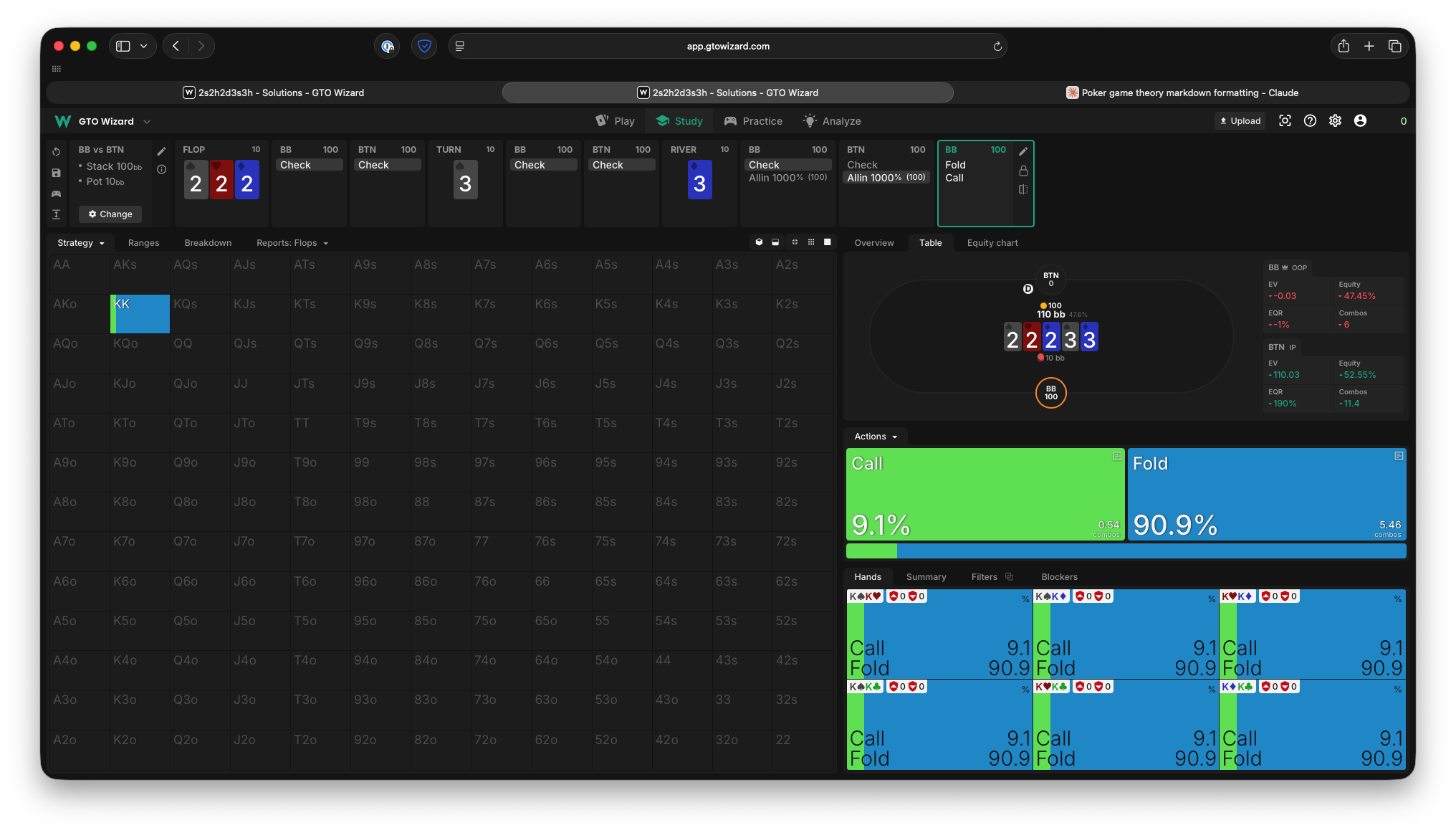

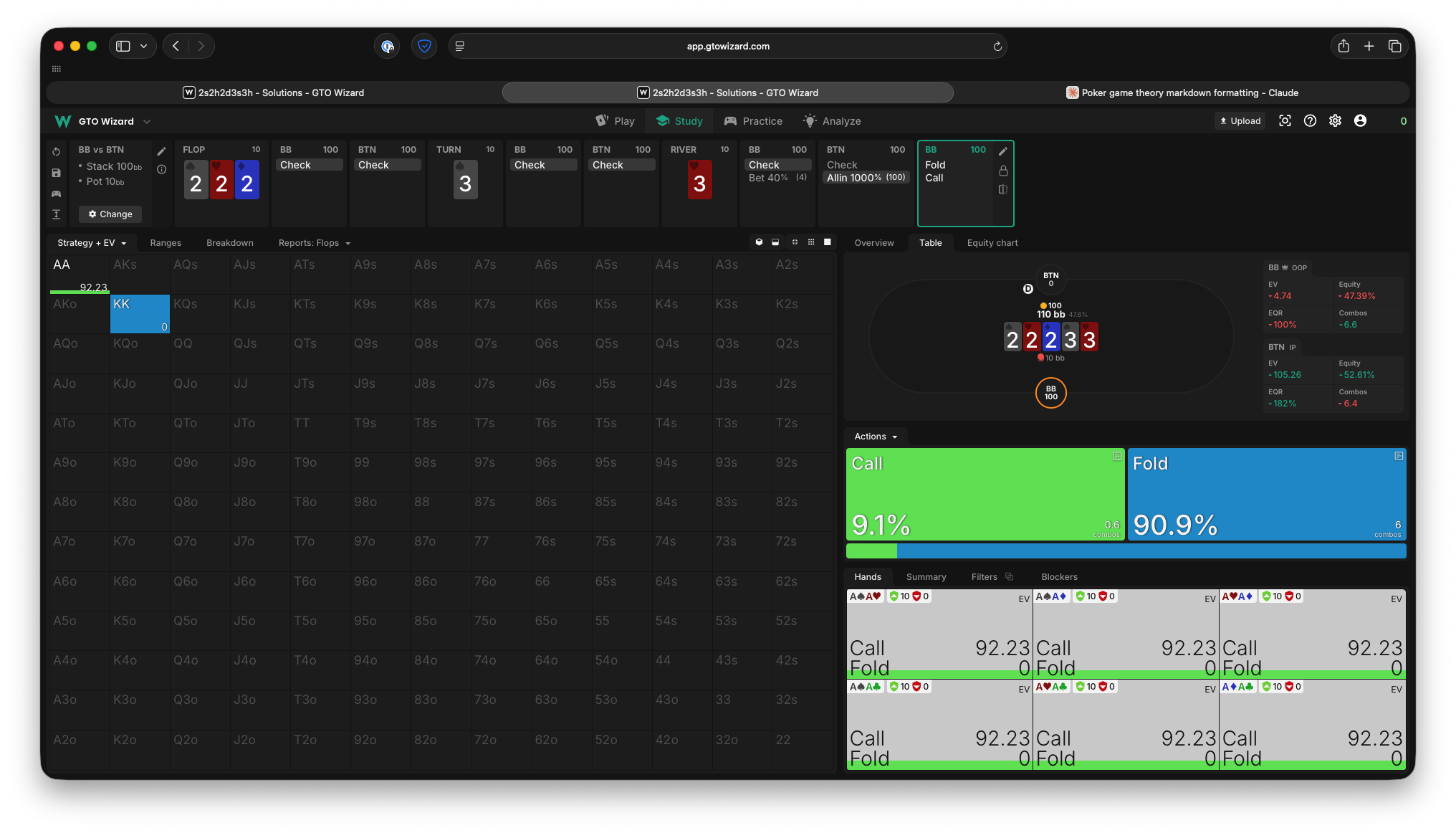

Remember our observation about EQR? When we get deeper, Ivey’s EV has increased to a whopping 95% of the pot (up from 75% with SPR 1), and he now bluffs QQ nearly always! Facing this bet, the optimal strategy is for Oscar to call only ~9% of the time.

Takeaway 1: The larger the stack-to-pot-ratio, the more EV a polar range will have against a condensed one. It becomes more important for OOP to have “traps” as we get deeper and deeper.

Takeaway 2: Remember, we win the whole pot whenever we bet. When we are perfectly polar (our value hands have 100% equity), our value hands will always bet, and our bluffs will bet with a frequency that makes the opponent indifferent to calling. We’re giving them worse odds when we bet larger, so we get to bluff more often, which means we win the whole pot more often and thus generate more EV.

Takeaway 3: Value hands bet a size according to their equity. Bluffs simply choose the same size as the value hands.

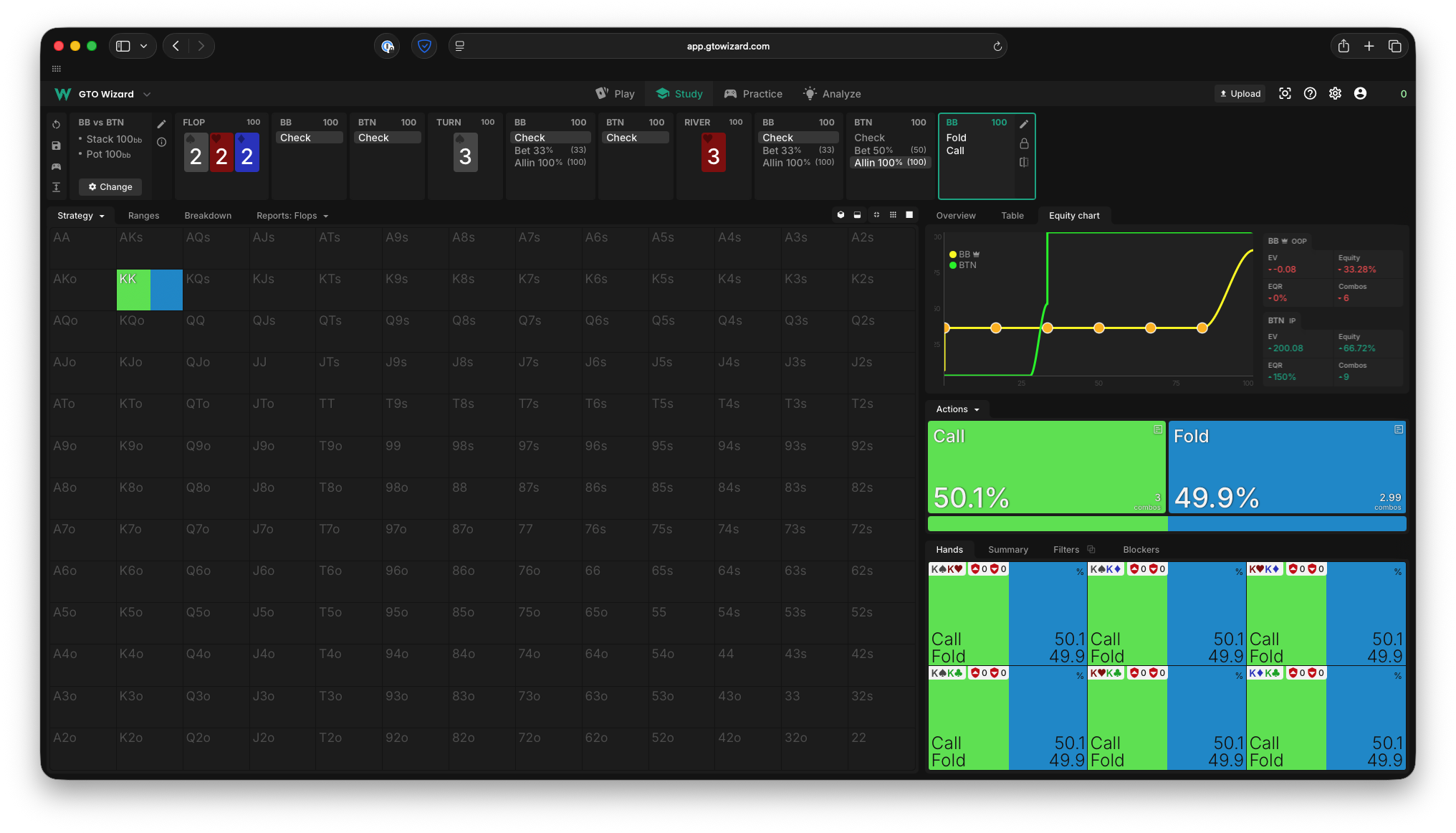

3. Oscar was pretty miserable in the previous example. Maybe traps are good? Let’s stick to 10 SPR, but check what happens if Oscar protects his range and has some traps. I added a sliver of AA chops to Oscar’s range, with 10% the weight of KK.

We should realize intuitively that it still wouldn’t make sense for Oscar to bet AA. What would be the point? The opponent would never call QQ!

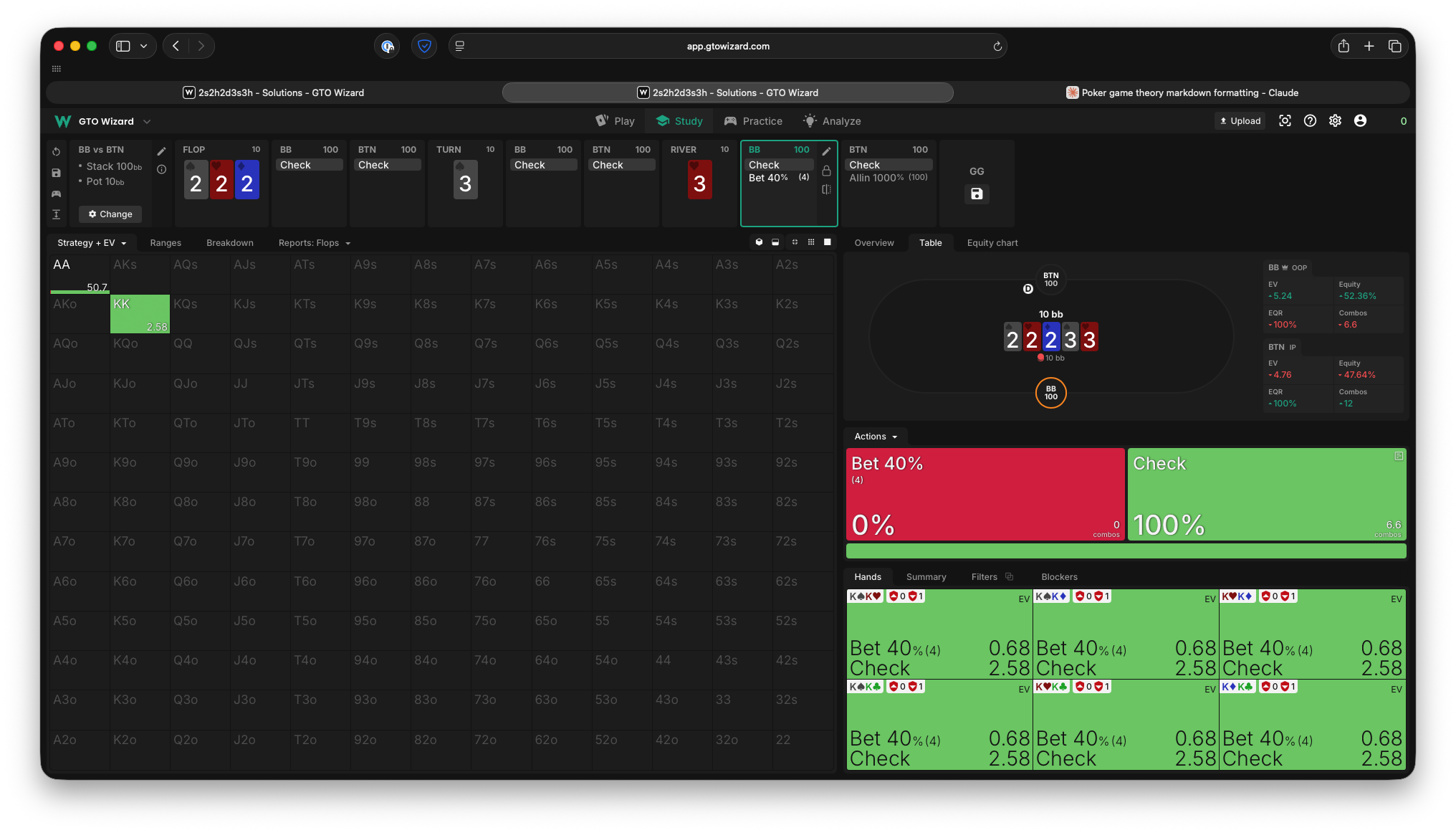

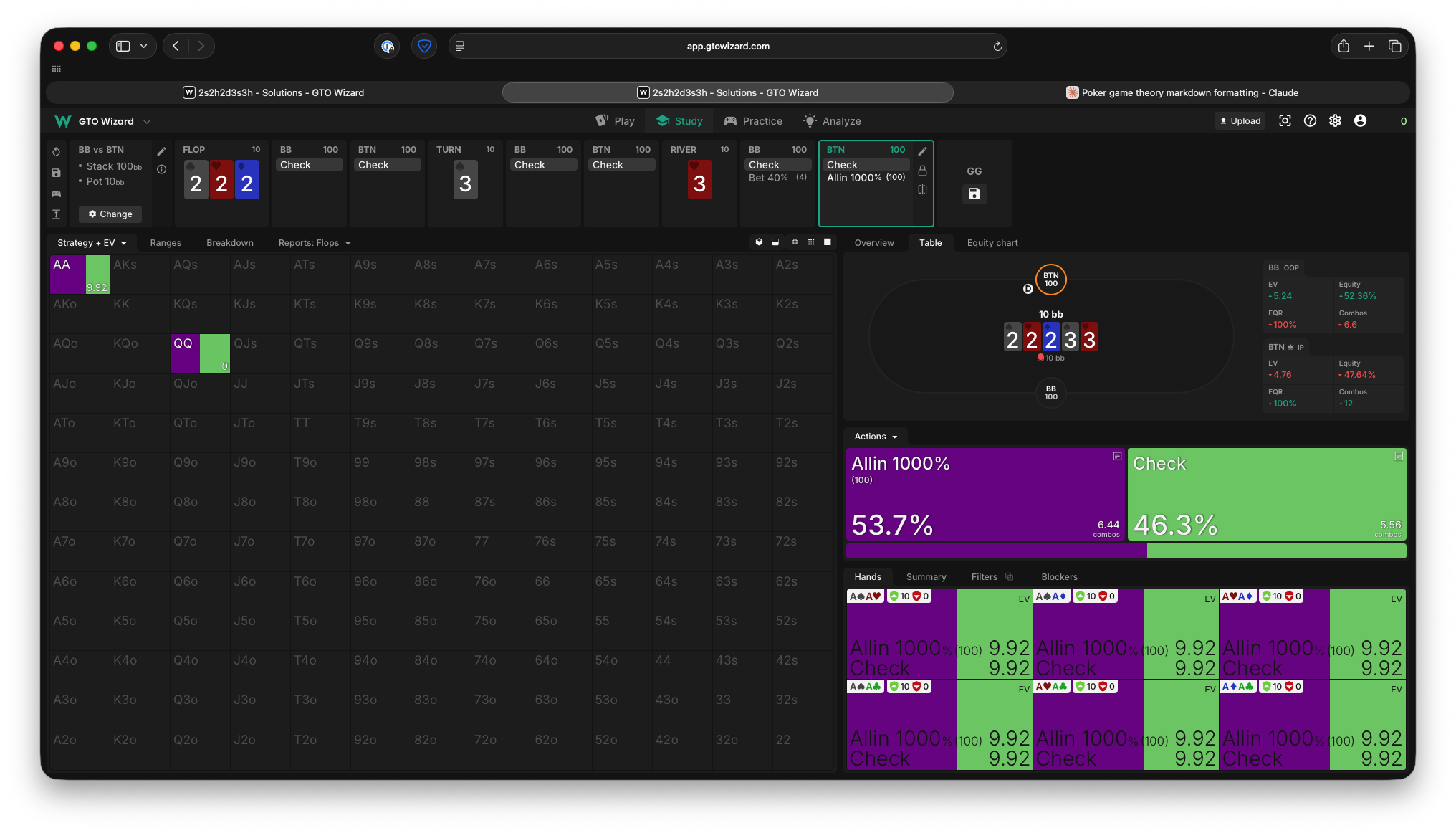

If you still restrict Ivey to playing a shove or check strategy, his EV completely plummets.

You’ll notice that he is actually indifferent to betting AA here! Given that Oscar only needs to defend about 9% of the time vs a 10x pot shove to make QQ indifferent, and he holds AA 9% of the time, Ivey never gets paid off by KK. This is really bad for his EV, and means that this 10x pot shove is larger than optimal for this scenario!

If you let the solver pick the size it wants, it starts using a 3x pot size bet instead. This smaller size forces the opponent to start defending KK, lets us bet AA always, and is the “right” size based on our equity of 90%. Our EV is back up to 72% of the initial pot (note how the tiny frequency of traps reduced this from 95% earlier, though!).

Takeaway 1: Why does GTO have traps? It gives us some “easy defends” and prevents the opponent’s range from being perfectly polar. You’ll sometimes hear poker players say things like “I thought my opponent was underprotected in this line, so I bluffed”. This isn’t a valid thought process!! There’s nothing at all that stops your opponent from calling with a bluff catcher if they believe you are just overbluffing. They absolutely do not need traps in order to just flick in a call and punish an overbluff.

There are two other valid things you could say though:

-

I thought my opponent would fold enough that my bluffs make more money by betting than giving up (overfold). Self-explanatory.

-

I thought my opponent didn’t have enough traps compared to theory, so I used a bigger size / bet with thinner value hands than the solver would. This allows me to force them into bluff-catching spots and thus win the whole pot in EV more often!

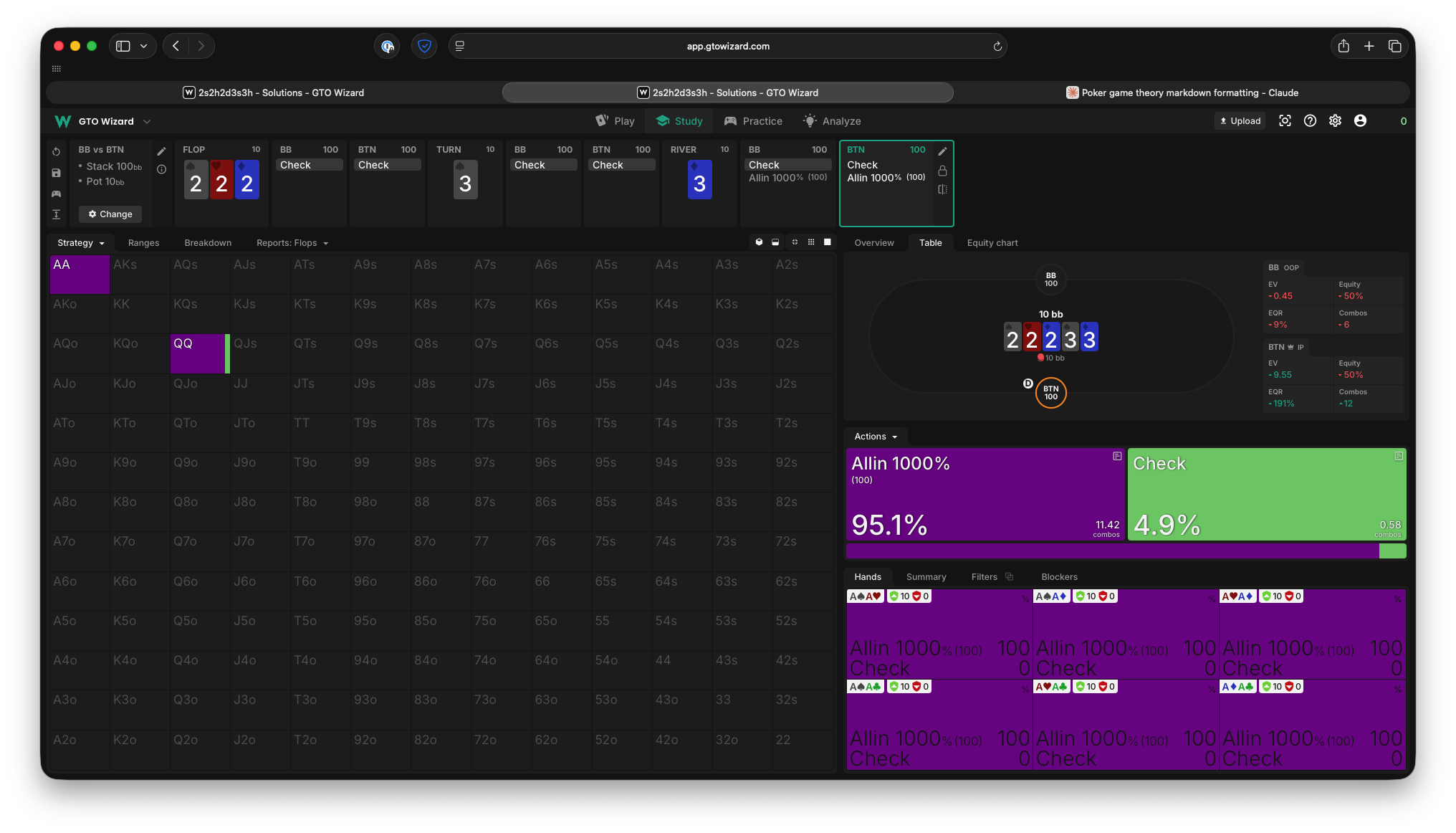

4. Let’s make our sim just a bit more realistic. I’m going to give the player’s equal ranges, more hands, and more bet sizing options. The river will still be a 10 SPR spot.

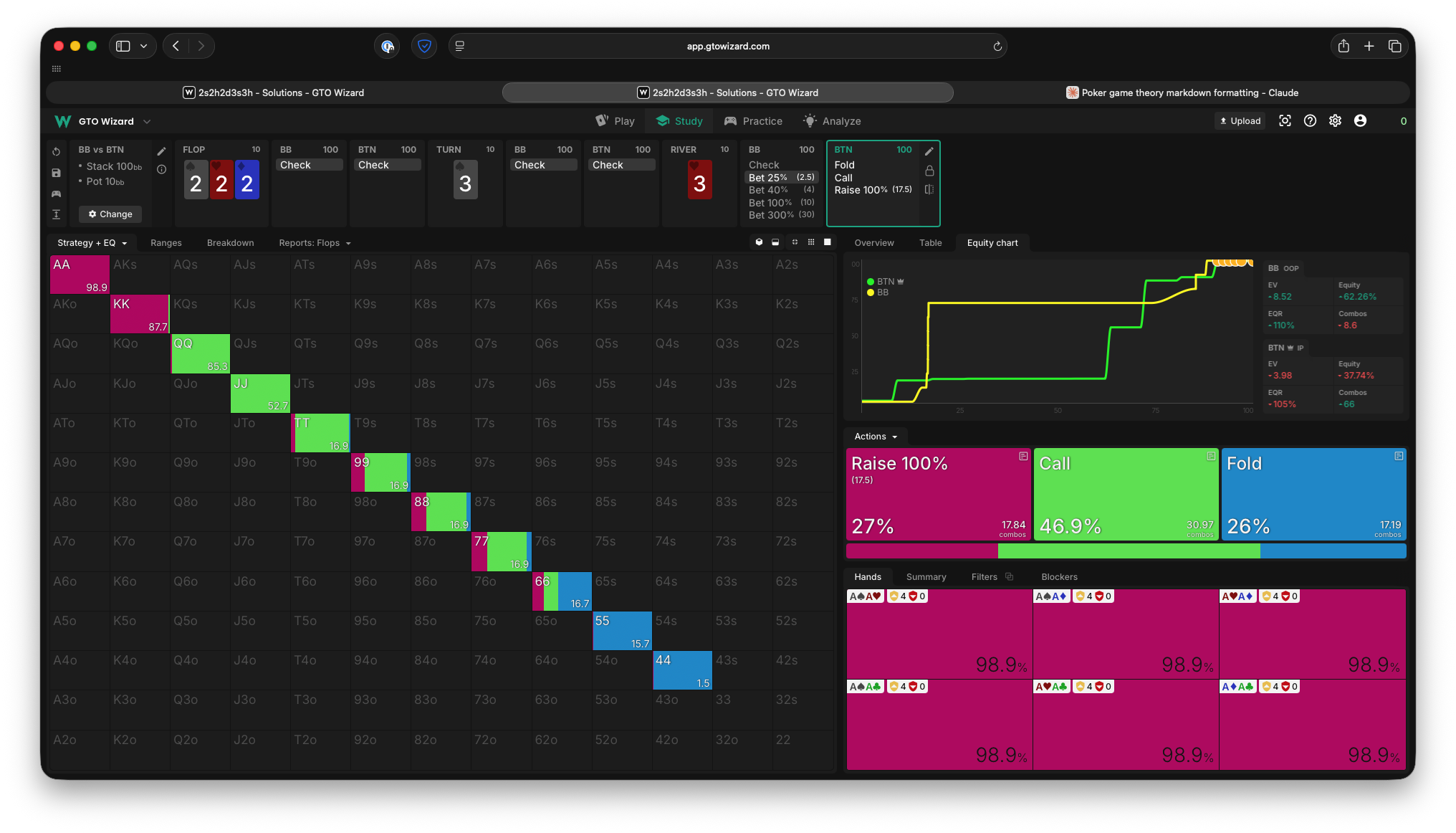

Okay, this starts to look a lot more complicated. But at its core the solution is just a more sophisticated version of the simple Nash we come up with before. The “nutted” hands often trap, expecting to face bets enough from other strong hands and force them into a bluff-catching spot after a check-raise. The non-nutted but still strong hands bet a size that forces the opponent to bluff catch with hands they beat. The mediocre hands check, hoping to get to showdown, with the plan to face a bluff-catching spot if they must. And the weakest hands either give up or choose bluff. The game tree is actually kind of sprawling here, but I’ll just show you the first Oscar node, and what Ivey’s response looks like facing the smallest bet.

Note there’s also a big difference between being in position vs out of position. In position closes the action, so they don’t need to be as worried about “protecting” their middling checking hands and also don’t gain anything by trapping the nuts. This is actually a much more central poker concept than it seems, and we’ll revisit this at some point.

Note: I may come back to this post and add some more examples, but I think it’s getting a bit long already. Potentially they’ll come never or in a later page.

What next?

All this was pretty neat, but it’s a little contrived. The above examples use weird ranges and focus on river decisions only, and thus don’t shed much light on how we should play real hands. Nevertheless, these concepts are so foundational that I think it was still worth spending some of our precious 25 hours of study time on, and I’ll pivot to focusing on some more practical advice going forward.

Give a man a cookie, and you feed him for a session. Teach a man some poker, and maybe next time he’ll provide the snacks!